Silicosis Associated Osteoporosis: An Emerging Equine Bone Disease

A progressive, debilitating, and ultimately fatal bone disease has been recognized in recent years to affect horses in California. The disease – termed silicate associated osteoporosis (SAO) - has a preference for bones of the upper portion of the limbs (e.g., scapula, pelvis), the ribs, and the vertebral spine. When mildly affected, horses appear to have an intermittent lameness without an identifiable cause. The lameness may affect one leg, several legs, or different legs at different times. When multiple legs and/or the spine are affected, horses can appear to have a generalized stiffness and reluctance to move. With disease progression, bones of the spine and upper portions of the front and hind legs become weak. Over the course of months to years the bones deform and sustain incomplete bone fractures that attempt to heal. Ultimately, a fracture may be severe enough to cause death or necessitate humane euthanasia.

Symptoms

Severely affected horses can be recognized by skeletal deformities. The scapula (shoulder region) begins to bow outwardly. This usually starts with one shoulder bowing initially, but often both shoulders are eventually affected. The back becomes markedly swaybacked in a relatively short period of time. The neck becomes stiff making turning the head and eating off the ground difficult, or ultimately impossible.

Diagnosis

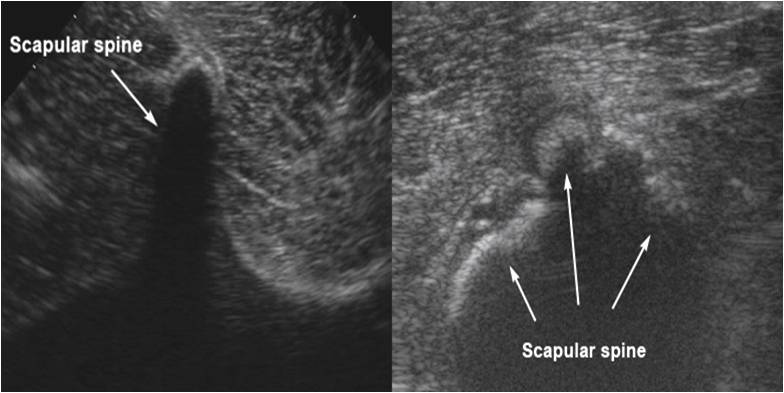

Diagnosis of Silicate Associated Osteoporosis (SAO) is confirmed by bone scans. Multiple abnormalities are identified in multiple bones of the upper portions of the legs, the vertebral spine, and the ribs. The results of routine blood tests are usually normal. Radiographs of the legs are not generally helpful in disease diagnosis because the bones in the lower part of the limbs are minimally affected. Good quality radiographs of the lower cervical vertebrae in the base of the neck may be useful for detection of bone changes in moderately to severely affected horses. Ultrasound examination of the scapula (shoulder blade) may demonstrate thickening of the scapular spine or evidence of a fracture.

Complications

Affected horses may have concurrent pulmonary disease. Many horses with SAO have lung inflammation associated with inhalation of cristobalite, a specific silicate crystal found in some environments. Horses with moderate to severe lung disease require extra effort to breathe. These horses may have an elevated breathing rate during rest, accentuated muscles in the chest and abdomen due to increased muscular effort to breathe, and flaring of the nostrils in an effort to obtain more air.